January 2018

The Environmental Data & Governance Initiative (EDGI) is an organization comprised of academics and non-profit employees that promotes open and accessible government data and information along with evidence-based policy making.

“Changing the Digital Climate” is the third of a multi-part series on the early days of the Trump administration. In this series, EDGI authors systematically investigate historical precedents for Trump’s attack on the EPA, consequences for toxic regulation and environmental justice, and changes to the public presentation of climate change.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

INTRODUCTION

A BRIEF OVERVIEW OF CLIMATE DENIALISM IN THE U.S.

THE ROLE OF THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT IN CLIMATE RESEARCH AND POLICYMAKING

CHANGES TO FEDERAL WEBSITES PERTAINING TO CLIMATE CHANGE

- Altering the Presentation of Climate Change on the White House Website

- Altering Information on International Climate Change Agreements and Partnerships

- Renewable Energy Versus Job Growth

- Non-Renewable Energy Sources and Their Effects on the Environment and Human Health

- Language Shifts: “Resilience” and “Sustainability” Instead of “Climate Change”

- Changes to Agencies’ Overall Presentation of Climate Change

IMPORTANCE OF ACCURATELY DESCRIBING FEDERAL WEBSITE CHANGES AND MEDIA PORTRAYAL

STATE AND LOCAL RESISTANCE TO TRUMP ADMINISTRATION CLIMATE CENSORSHIP

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

EDGI’s website monitoring working group monitors changes to tens of thousands of federal webpages that relate to environment, climate, and energy. In the first year of the Trump administration, we have observed alterations to many federal agency Web resources about climate change. Although there is no evidence of any removals of climate data, we have documented overhauls and removals of documents, webpages, and entire websites, as well as significant language shifts.

- The Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) removal and subsequent ongoing overhaul of its climate change website raises strong concerns about loss of access to valuable information for state, local, and tribal governments, and for educators, policymakers, and the general public.

- Several agencies removed or significantly reduced the prominence of climate change Web content, such as webpages, documents, and entire websites, and the White House omitted climate change as an issue highlighted on its website.

- The Department of State, Department of Energy (DOE), and the EPA removed information about the federal government’s international obligations regarding climate change, downplaying U.S. involvement.

- Descriptions of agency priorities shifted to emphasize job creation and downplay renewable fuels as replacements for fossil fuels. At the DOE, mentions of “clean energy” and explanations of harmful environmental impacts of fossil fuels were also removed.

- Language about climate change has been systematically changed across multiple agency and program websites. In many cases, explicit mentions of “climate change” and “greenhouse gases” have been replaced by vaguer terms such as “sustainability” and “emissions”.

While we cannot determine the reasons for these changes from monitoring websites alone, our work reveals shifts in stated priorities and governance and an overall reduction in access to climate change information, particularly at the EPA.

These documented changes matter because they:

- Make it more difficult for the scientists, policymakers, historians, and the public to access the results of years of scientific and policy research funded by tax dollars.

- Make it harder for state, local, and tribal governments to access resources designed to help them adapt to and mitigate the harms of climate change. For example, the EPA removed over 200 climate webpages for state, local, and tribal governments.

- Diminish our democratic institutions, such as notice-and-comment rulemaking, which depend on an informed public. The removal of the EPA’s Clean Power Plan website has broad implications.

- Can confuse the public if significant changes are not sufficiently justified. Alterations to the U.S. Geological Survey’s search engine generated public confusion.

- Contribute to broader climate denialist efforts that obscure and cast doubt on the scientific consensus on climate change, hampering critical efforts to mitigate and adapt to climate change.

What are EDGI’s Recommendations?

- Transparency. Especially for major website overhauls, but for smaller updates to webpages as well, agencies should detail the scope of the pages that will be affected and clearly explain the reason for planned alterations in a public statement, well in advance of the changes actually being made.

- Responsible Web archiving. Federal agencies should not alter or reduce access to Web content before they have created a log to thoroughly document their intended changes and ensured that the content is preserved and, for significant alterations, made accessible through a public archive.

- Valuing Web resources. Web resources should be valued in terms of their educational importance, how much they enable historical understanding, and their advancement of scientific and policy research. Records schedules and records governance broadly should reflect these uses.

- Distributed Web archiving. Federal agencies should work with growing civil society movements to rethink the way we organize, steward, and distribute data, Web resources, and online information.

- Environmental data justice. Federal environmental agencies should work to create digital infrastructure through which communities can determine what kinds of data are collected and presented about them, in response to which issues. This includes proactive efforts to identify and accommodate those who access federal Web information, as well as offering communities the right to refuse consent to data collection.

II. INTRODUCTION

Would the U.S. government give up its role in combating climate change? This was one of the primary concerns expressed by climate policy experts, domestic and international leaders, and concerned citizens in the wake of the 2016 presidential election.[1] In addition to providing political and financial support for mitigation and adaptation globally, the U.S. government produces and funds much of the data upon which the global climate science community depends. Federal agencies serve a critical and authoritative role in analyzing and communicating climate science, which informs science-based policy. The U.S. has reduced its own contribution to climate change in recent years as companies, states, and the federal government have instituted new policies targeting greenhouse gas emissions.[2] For these reasons, and because of its economic and political leadership on the international stage more broadly, U.S. policy shifts have implications far beyond its borders.

As a candidate, Mr. Trump referred to climate change as “a hoax”, and as President his actions have been consistent with that view.[3] The transition teams he selected for federal environmental agencies and his eventual cabinet choices, such as EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt, included many who deny the scientific consensus that humans are causing climate change.[4] Since taking office, both Administrator Pruitt[5] and Secretary of Energy Rick Perry[6] have affirmed their skepticism, rejecting the consensus that CO2 is the primary driver of climate change.

It is thus not surprising that there have been substantial climate policy shifts during the first year of the Trump administration. The reversal of regulations on coal mining, oil and gas drilling, and thousands of power plants began in March with a sweeping executive order, which also initiated a review of the Clean Power Plan.[7] On October 10, 2017, the EPA began its formal repeal of the plan.[8] President Trump decided to withdraw from the landmark Paris Agreement, meaning the U.S. is now the only country in the world not committed to “pursue efforts to limit the [global average] temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, recognizing that this would significantly reduce the risks and impacts of climate change,” after Nicaragua and Syria announced that they would sign on to the accord.[9] In withdrawing, President Trump ignored climate experts who warn that increasing magnitudes of warming increase the likelihood of severe, pervasive, and irreversible consequences, including extreme weather events, drought and forest fires.[10] Going further, in the new National Security Strategy released in December 2017, the Trump administration broke norms by removing climate change from a list of global threats.[11]

Since President Trump’s inauguration, EDGI has been monitoring tens of thousands of federal environmental websites to assess changes to the public’s access to information and Web resources, and track rhetorical shifts. This work is an unprecedented effort to hold the federal government accountable for changes in public access to information that could easily have evaded scrutiny in the past.

Federal websites are an important interface between the public and the government, helping people better understand climate change and ways to address it via adaptation and mitigation. These websites provide the public access to scientific results funded by their tax dollars, support democratic process by serving as an authoritative and easily accessible source for the public to educate themselves on key climate change issues, and provide a bulwark against efforts to obscure or cast doubt on accepted science on politically sensitive topics. Alterations to these federal websites can thus have very broad consequences.[12]

It is important to emphasize that EDGI’s website monitoring efforts have thus far found no removal or deletion of climate data sets from federal websites under the Trump administration. Instead, we have found substantial shifts in whether and how the topic of climate change and efforts to mitigate and adapt to its consequences are discussed across a range of federal agencies’ websites. Perhaps most importantly, we have found significant loss of public access to information about climate change.

In the sections that follow, we first provide a brief overview of climate denialism in the U.S. and describe the federal government’s key role in national and international climate science as context for the changes EDGI has observed. We then present particular changes to federal websites, how shifts in language and access to information affect the public presentation of climate change, and how in some cases they have been misrepresented in the media. We then describe a range of ways in which state and local governments have resisted loss of public information on climate change, and conclude by addressing what is at stake when the information on federal websites is altered or removed and recommending more just and accountable practices for digital information governance.

III. A BRIEF OVERVIEW OF CLIMATE DENIALISM IN THE U.S.

The alteration of climate change content on federal websites extends a longer campaign to “manufacture doubt” on human-caused (or anthropogenic) climate change. Since the 1980s, fossil fuel interests, from companies and think tanks to media and politicians, have drawn upon strategies forged by the tobacco and other threatened industries to cultivate public skepticism about climate change.[13] Over the past two decades, this campaign has gained in confidence, clout, and momentum, to the point that, even prior to the 2016 election, it had effectively precluded many meaningful legislative or policy changes to regulate fossil fuel emissions and encourage alternative energy sources, in order to protect industry profits.

The climate change denial movement in the U.S. has deep roots in older efforts by oil, gas, tobacco, and chemical industries to counter scientific research that raised hard questions about the products they sold. As Naomi Oreskes and Erik Conway have explained in compelling depth,[14] the post-World-War-II tobacco industry pioneered new ways of discrediting health studies that demonstrated the connection between tobacco use and cancer or other health risks. Seeking to intervene in the field of scientific debate itself, they funded counter-research by a shrinking number of sympathetic scientists, demanded a level of certainty that scientists rarely possess, and exaggerated the uncertainty of existing science. They also sought a broader public audience for their contrarian messages by creating echo chambers of think tanks and other organizations they quietly funded, as well as consolidating ties to media outlets.

All of these tactics have been taken up and amplified by the campaign to manufacture doubt about anthropogenic climate change, even as the supporting scientific evidence and consensus for it has become ever more solid.[15]

Contemporary alterations of climate information are not merely the culmination of a multi-decade crescendo of denialism but also part of a wider practice of censoring science that is seen to be at odds with short-term economic gains. In recent years, the actual or attempted muzzling of federal scientists in Canada, Australia, Great Britain, and the United States has been the most common means of science suppression.[16] In the case of the George W. Bush administration, such actions provided cover for political interference in the production of climate change reports and communication, despite the administration’s acknowledgment of the importance of reducing greenhouse gas emissions.[17]

The alterations and removal of information that we document below clearly demonstrate that the once-fringe effort to seed doubts about climate science has been mainstreamed into the Executive Branch of the U.S. government. Climate deniers have won influential posts across all the major environmental agencies, and the agencies’ websites increasingly reflect denialist beliefs. These changes matter because they make it easier to mislead the public about climate change, since federal websites have long been viewed as authoritative sources of environmental information. Climate denialists’ historic political achievement elevates the manufacture of doubt to the level of state-sponsored censorship.

IV. THE ROLE OF THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT IN CLIMATE RESEARCH AND POLICYMAKING

The federal government’s substantial climate-related Web presence is not surprising, given the extensive U.S. activities pertaining to climate change science and policy across many federal agencies, offices, and programs, as well as internationally through foreign assistance. According to the Office of Management and Budget, federal funding for climate science, technology, adaptation, and international assistance was $11.6 billion in 2014, an increase from $2.4 billion in 1993, with an additional $26.1 billion for climate change programs and activities provided by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act in 2009.[18]

The EPA, for instance, is responsible for climate-related work that includes monitoring and data collection efforts as well as policy and adaptation assistance. The EPA’s Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program[19] collects and publishes data regarding emissions from U.S. facilities that emit large quantities of greenhouse gases. The EPA’s Office of Research and Development works to understand and provide sustainable solutions to the environmental and health impacts of climate change.[20] Other EPA efforts have included legislative analysis, economic modeling, and establishing frameworks for state, local, tribal, and international community climate action.[21]

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) are responsible for major data collection operations, including numerous satellite programs.[22] The Department of the Interior (DOI) runs eight National Climate Change and Wildlife Science Centers across the country that assess the vulnerability of various species and habitats to climate change and connect models of climate change to ecological effects.[23] DOI’s Bureau of Land Management (BLM) conducts Rapid Ecoregional Assessments to help communities better adapt to environmental change and works on climate change mitigation through renewable energy projects, particularly wind, solar, and geothermal.[24]

The DOE’s 17 National Laboratories host cutting-edge climate and atmospheric research programs, in addition to advancing renewable energy and energy efficiency research.[25] The DOE’s Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, which promotes a global clean energy economy and supports the development of renewable technologies, received $2.89 billion for fiscal year 2017 and $2.03 billion the prior year.[26]

These are just some examples of the expansive scope of the federal government’s involvement in climate research and policymaking. Federal websites reflect the government’s investment in climate-related work, as well as the priorities of individual agencies and offices, and are treated as authoritative sources for data and information on climate change.

V. CHANGES TO FEDERAL WEBSITES PERTAINING TO CLIMATE CHANGE

EDGI has released a series of reports on changes to federal environmental websites during the first year of the Trump administration. Drawing on these reports, we herein summarize trends in how the treatment of climate change across federal websites has changed. While no datasets have been removed, we have found significant shifts in stated climate policies, how climate change is described, how adaptation and mitigation efforts are framed, and overall public access to information on climate change.

Altering the Presentation of Climate Change on the White House Website

The White House website was the first federal site to be changed under President Trump’s tenure. President Obama’s White House site was archived and remained accessible online, as was the case in the Clinton-Bush and Bush-Obama transitions,[27] and a new site was put in place by the Trump administration. The new website omitted major topics highlighted on the Obama-era site, including climate change.

Many press accounts misrepresented what had occurred, stating or implying that the new administration had deleted information or data and failing to mention that the Obama administration site was archived and publicly available.[28] However, the changeover left the Web scattered with dead links to old White House pages referencing climate-related documents and information. Because these links were not set up to redirect to the new URLs in the archived Obama White House site, the information they contain is only available to people able to find the archives through some other means, significantly reducing the accessibility of these climate change resources.

In December 2017, President Trump launched a redesigned White House website. Almost a year into the new administration, the website, unlike President Obama’s,[29] makes no mention of climate or climate change on its “Energy & Environment” page.[30]

The Office of Science, Technology, and Policy (OSTP), responsible for providing analysis of scientific and technological federal policies and programs to the President, has yet to rebuild its portion of the White House website,[31] which under President Obama included an “Initiatives” section on “Combating Climate Change.”[32] The lack of a prominent OSTP Web presence may be explained by the fact that President Trump has yet to appoint a White House science advisor, who, among other duties, leads the Office.[33] On November 16, 2017, seven senators sent a letter to President Trump urging him to appoint a science advisor and fill other key open OSTP positions.[34]

The lack of White House attention to climate change from the outset of the Trump presidency and the continued disregard for these issues, coupled with the lack of key staff working on climate issues, send a clear signal that climate action is not a priority for this administration. Moreover, poor Web governance practice has broken links to Obama-era climate Web resources across federal and nonfederal websites, diminishing the public’s ability to engage with information about U.S. climate efforts.

Altering Information on International Climate Change Agreements and Partnerships

In response to growing concern over climate change, the international community has begun working together on mitigation and adaptation efforts such as reducing greenhouse gas emissions and maintaining economic security, and has established important treaties and agreements. Under the leadership of President Obama, the U.S. helped negotiate and establish the Paris Agreement. President Obama’s 2013 Climate Action Plan included bilateral initiatives with major emitting countries, including China and India, to address global climate change.[35]

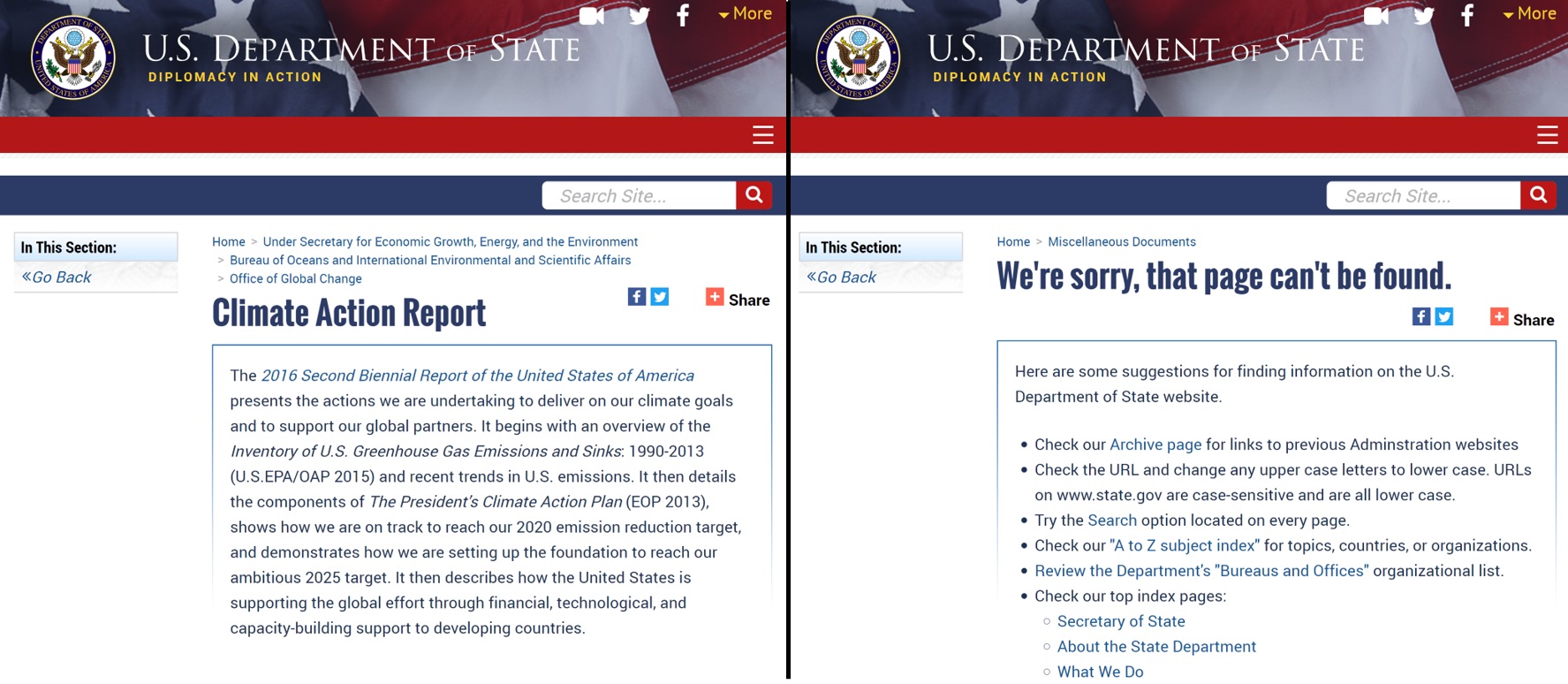

Soon after Mr. Trump’s inauguration, federal websites began downplaying U.S. involvement in international climate action and removing documents pertaining to international agreements. The State Department’s Office of Global Change, for example, updated text and links and removed pages with reports pertaining to climate change. Notably, the 2010, 2014, and 2016 Climate Action Reports were removed from the State Department site (Figure 1).[36] Though the reports are stored in State Department website archives, their former URLs do not redirect to the archived pages’ new URLs, as for the White House pages above, significantly reducing access to the reports. The production of these reports fulfills the U.S. government’s obligation under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)[37] to detail actions taken to mitigate effects of climate change. Their removal signals that the administration may pull out of the UNFCCC. Moreover, the removals obscure that such a commitment to the UNFCCC exists in the first place, making it more difficult for citizens to hold the administration accountable for abiding by international treaties and current U.S. government policy.

The Montreal Protocol is an international agreement, ratified by 196 countries including the U.S., to reduce the emission of ozone-depleting substances. Its hydrofluorocarbon (HFC) amendment is intended to reduce the use of HFCs, a particularly potent greenhouse gas. Pages describing the Montreal Protocol titled “Phasing Down HFCs” and “International Statements on HFCs”[38] were removed from the State Department website. Informing the public about HFCs and efforts to curb their emissions is important as these gases are found in air conditioners and refrigerators and contribute to climate change thousands of times more than carbon dioxide on a molecule-to-molecule basis.[39] These pages, too, have been stored in the difficult-to-access State Department website archives. As with the Climate Action Reports described above, removing these pages reduces access to important information and obscures the current international commitments of the U.S. government to treaties already or soon to be in force.

The description of the State Department’s Office of Global Change was also updated, removing a concluding sentence: “The working partnerships the United States has created or strengthened with other major economies has [sic] reinforced the importance of results-driven action both internationally and domestically and are achieving measurable impacts now to help countries reduce their long-term greenhouse gas emissions.” It was replaced with a sentence mentioning “adaptation” and “sustainable landscapes”.[40] Coupled with the page removals described above, this type of change in rhetoric significantly shifts the State Department’s presentation of the impact and scope of international climate change agreements.

That the Office of Global Change site no longer links to a page about the Special Envoy of Climate Change is consistent with the State Department’s move to eliminate the position.[41]

The EPA website also saw rapid changes relating to international climate relations. Within days of the inauguration, the EPA’s “Federal Partner Collaboration” page describing its work with federal, state, tribal, local, and international partners on climate change was retitled “EPA Adaptation Collaboration”, and significant sections on that page were removed or rewritten. Among the removals were links to webpages on President Obama’s Climate Action Plan, an executive order on preparing for effects of climate change, the Council on Environmental Quality’s climate change resilience efforts, and the tribal Environmental General Assistance Program. On the EPA’s “International Climate Partnerships” page, a paragraph was removed that affirmed the U.S. commitment to the objectives of the UNFCCC, in particular to “stabilizing greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that prevents dangerous human-induced interference with the climate system”.[42]

The DOE page on climate change removed a video about the Paris climate accord as well as links to climate websites, such as NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information and the National Climate Assessment, which describes impacts of climate change on the U.S.[43] These changes came shortly after Politico reported that DOE employees in the Office of International Climate and Clean Energy were told to avoid the terms “Paris Agreement”, “climate change”, and “emissions reduction” in written communications.[44]

These DOE and EPA webpage changes, echoing the State Department's alterations to international climate change information, suggest a pervasive international agenda shift across federal agencies. While we cannot discern if these changes were directed from a centralized source, such as the Executive Branch, or if agencies independently decided to align with what they believed was the administration’s policy, these systematic changes provided early signals of future international climate policy decisions, such as the eventual withdrawal from the Paris Agreement.

Renewable Energy Versus Job Growth

Investment in renewable energy can mitigate the negative effects of climate change and provide energy security, promote social and economic development, and reduce negative environmental and health impacts.[45] Yet under the Trump administration, descriptions of agency office priorities began to downplay the importance of renewable energy.

For example, the DOE’s Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (EERE) office updated language and links on its Bioenergy, Wind Energy, and Vehicle Technology Office websites, reducing emphasis on renewable energy in favor of fossil fuels.[46] The sentence, “wind power is an emission-free and water-free renewable energy source that is a key component to the Administration’s renewable electricity generation goals,” was removed from the Wind Energy website. On the Vehicle Technology Office page, the phrase “transportation technologies that will reduce the use of petroleum” was changed to “transportation technologies that will strengthen US energy security, economic vitality, and quality of life.” And the sentence, “through our efforts to develop biobased products and increase biopower generation, we’re helping to replace the whole barrel of oil” was rewritten, omitting the clause, “we’re helping to replace the whole barrel of oil” on a Bioenergy Technologies Office page.

The changes to these renewable energy pages also reflect an increased emphasis on U.S. jobs and economic growth. For example, the following sentences were added: “Wind energy currently supports more than 100,000 U.S. jobs, and wind turbine technician is the nation’s fastest-growing occupation” and, on the Bioenergy page, “the potential production could, in turn, directly generate $30 billion in revenue and 1.1 million jobs in a variety of sectors including farming, plant operations, scientific research, and product and equipment design.”

The DOE’s Office of Technology Transition (OTT) was established in 2015 to develop the agency’s policy for improving the marketplace impact of its research investment and boosting private sector investment in renewable technologies. Within OTT, the Clean Energy Investment Center changed its name to the Energy Investor Center (EIC). The center's renaming occurred as the term "clean energy" was removed throughout the then CEIC page, and multiple links, including several pertaining to clean energy, were removed from an OTT page describing EERE’s Technology-to-Market Program.[47] Reporting by The Washington Post found that these changes were initiated by the career staff and not by the Trump administration.[48] How the name and website changes reflect an altered agenda on renewable energy remains to be seen.

Under Secretary Ryan Zinke, the DOI’s top-level energy page was rebranded to remove emphasis on renewable sources of energy.[49] The first paragraph on the previous version of the page used to warn that “our dependence on foreign oil threatens our national security, our environment and our economy.” The page detailed a list of energy sources that the U.S. relies on, beginning with renewables and stating that, “as part of securing America’s energy future, we must move our nation toward a clean-energy economy.”

The new version of the page, titled “American Frontier,” removed the detailed description of energy sources and seemed to put conventional sources of energy on equal footing with renewables. The connection between American energy policy and job growth was emphasized with the addition of the following sentences: “American energy resources create jobs and revenue. With proper policies that foster growth and local input, the Department provides opportunities for new jobs and revenue for state, local, federal, and Tribal governments.” While the new page retained links to other DOI pages with resources on energy, both renewable and non-renewable, the shift in presentation and language distinctly supports the Trump administration’s agenda to undercut the importance of renewable energy.

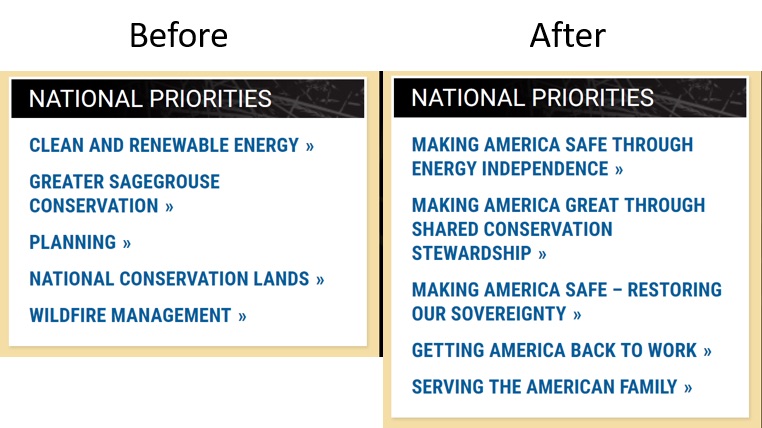

Also at the DOI, the BLM no longer lists “Clean and Renewable Energy” as a national priority, but instead highlights “Making America Safe Through Energy Independence” and “Getting America Back to Work”.[50]

These changes across the DOE and DOI Web domains present a consistent perspective: renewable energy sources should not be considered a replacement for fossil fuels and are valuable to the extent that they bolster the U.S. economy, not because of their environmental and climate benefits.

Non-Renewable Energy Sources and Their Effects on the Environment and Human Health

Across various federal agencies, descriptions of the effects of using non-renewable fuels, such as coal, oil, and natural gas, were altered, generally reducing the emphasis on their social and environmental costs.

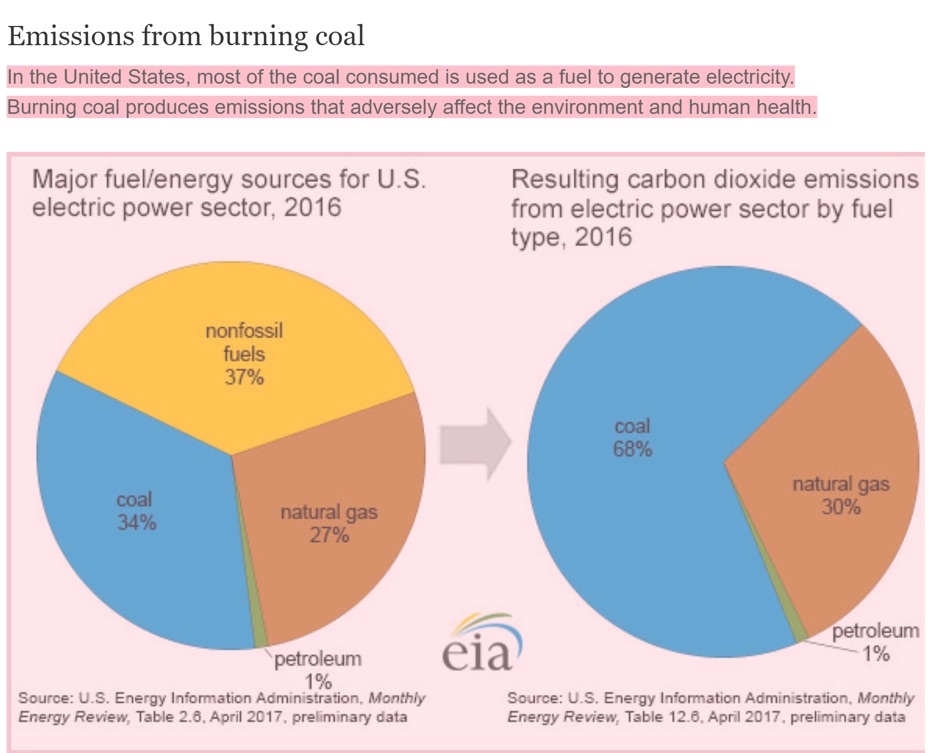

Removal of sentences and graphs and subtle changes to language were observed on the Energy Information Administration’s (EIA) Energy Kids website.[51] On a page discussing coal energy, a plot quantifying CO2 emissions by fuel type was removed, along with the following sentences: “In the United States, most of the coal consumed is used as a fuel to generate electricity. Burning coal produces emissions that adversely affect the environment and human health” (Figure 3). Across the website, the word “impacts” was systematically changed to “effects”, for example: “impacts of coal mining” became “effects of coal mining,” and “reducing the environmental impacts of coal use” was changed to “reducing the environmental effects of coal use.” Importantly, EIA is an independent part of the DOE, meaning its administrator does not need approval from any other government employee, not even the Executive Office, prior to releasing any publication.[52] In fact, after a ProPublica article attributed the changes to the Trump administration, EIA released a press statement explaining their independent position in the government and claiming that there was no external interference.[53]

Every two years, the Government Accountability Office (GAO), also an independent agency, identifies program areas that are high risk due to “vulnerabilities to fraud, waste, abuse, and mismanagement, or are most in need of transformation,” and maintains a list on its website. In the most recent assessment, the GAO changed the framework within which federal oil and gas resources are discussed and rewrote their page accordingly. Most notably, a section on environmental and public health risks from shale oil and natural gas production was removed, including the sentence “Oil and natural gas development pose inherent environmental and public health risks, and studies have generally found that the potential long-term, cumulative effects of shale development have not been examined.” Expanding the focus on job creation and economic benefits, the introduction now states that oil and gas resources “provide an important source of energy for the United States; create jobs in the oil and gas industry; and generate billions of dollars annually in revenues that are shared between federal, state, and tribal governments”.[54]

These website changes come as civil society actions against fossil fuels pick up speed. Twenty-one youth plaintiffs are suing the federal government over climate change, arguing that supporting fossil fuels and greenhouse gas emissions has violated the youngest generation’s constitutional rights.[55] In a reversal of last year’s vote, ExxonMobil shareholders approved a proposal to disclose analyses of the ways in which global climate change guidelines will affect the oil company’s business.[56] Discussions of climate change are happening all over the world, in corporate offices, in living rooms, and on the streets. However, that discussion is notably absent in the Executive Branch, and information to support those discussions is being reduced and obscured. The language changes and reduction in access to information detailed above undermine the open discussion of climate change and how fossil fuels impact the environment and society.

Language Shifts: “Resilience” and “Sustainability” Instead of “Climate Change”

In some cases, agency programs and offices have shifted the terminology that they use to present climate change to the public, often replacing straightforward language with vague terms.

An EPA program called Climate Ready Water Utilities was renamed Creating Resilient Water Utilities, maintaining the same acronym (CRWU) and URL. On the new program page, all 19 mentions of “climate” were removed. The program’s earlier mission "to provide the water sector...with the practical tools,

training, and technical assistance needed to adapt to climate change by promoting a clear understanding of climate science and adaptation options" seems to have changed as well. The current CRWU webpage text states that the program "provides drinking water, wastewater and stormwater utilities with practical tools, training and technical assistance needed to increase resilience to extreme weather events".[57] Beyond messaging, it remains unclear whether and how CRWU’s operations have changed.

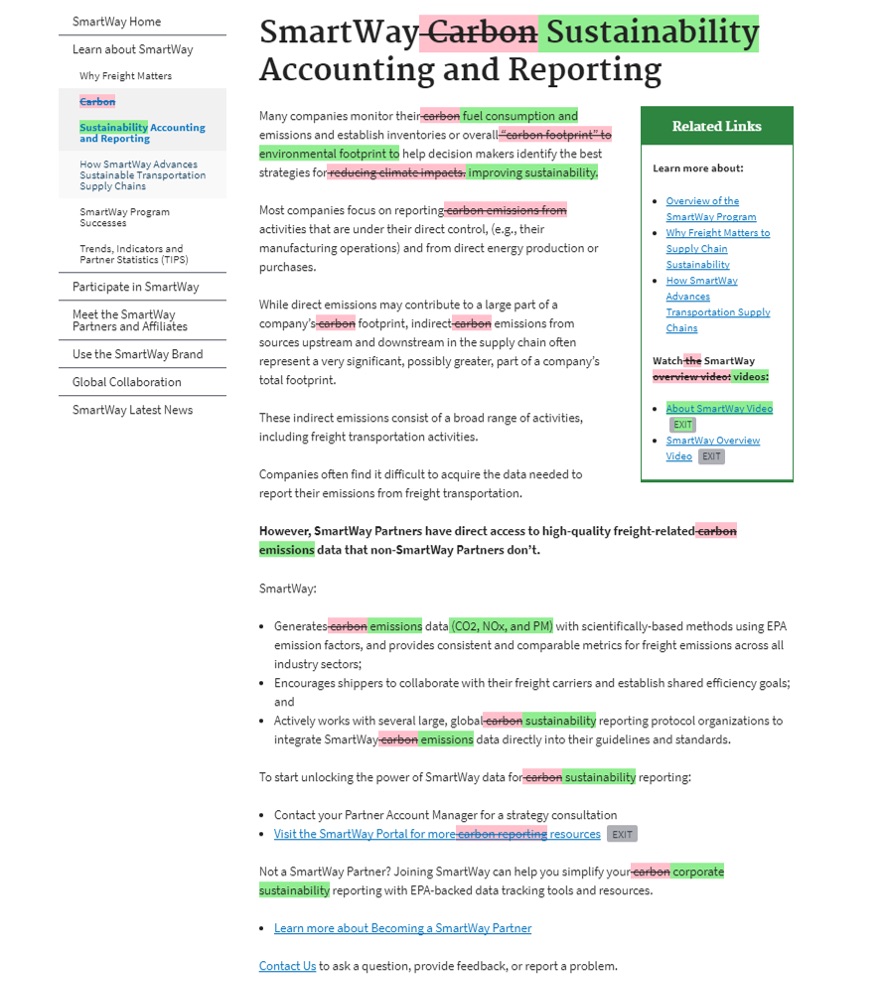

Also at the EPA, climate and emissions language was altered on the website of the SmartWay program, which was established to help companies improve supply chain sustainability by measuring and benchmarking freight transportation emissions. Terms like “sustainability” and “emissions” replaced mentions of “carbon.” A section titled “The science is clear - greenhouse gas emissions from all sources must decrease,” was entirely removed (Figure 4). Descriptions of the EPA’s international work with the United Nations Environment Programme’s Climate and Clean Air Coalition and links to the UN website were also removed (Figure 5).[58]

At the Department of Transportation (DOT), the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) changed language, page titles, and employee descriptions across multiple pages for its program on the environmental effects of transportation. FHWA renamed what was previously known as “The Sustainable Transport and Climate Change Team” to “The Sustainable Transportation and Resilience Team” on December 15, 2016.[59] A spokesperson for the agency told the The Washington Post that the team name was changed “after several weeks of internal discussions by FHWA’s Associate Administrator for Planning and Environment to more accurately reflect our agency’s emphasis on resilience activities.” The program’s website, however, continued to be edited throughout the Trump administration’s early months. Page banners were systematically changed from “Climate Change,” “Climate Adaptation,” and “Climate Mitigation” to “Sustainability.” Page titles changed from “Climate Change and Transportation” to “Sustainable Transportation,” “Adaptation” to “Resilience,” and “Greenhouse Gas Mitigation & Energy” to “Energy and Emissions.” In descriptions of the team’s duties, all four mentions of greenhouse gases, “GHG,” were removed.[60]

The term “greenhouse gases” has been removed or replaced on other agency websites as well. The State Department’s Office of Global Change page was rewritten, now without mention of the term. On the EERE’s Bioenergy Technology Office page, “greenhouse gases” was removed in multiple places and, in one instance, replaced by the term “harmful emissions.” As not all emissions are greenhouse gases, it may actually be more accurate to use the broader term, but the widespread removal and replacement of the term “greenhouse gases” may signify that agency officials want to distance their offices from association with climate change issues.

The Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Indian Affairs Tribal Climate Resilience Program (TCRP) changed its name by removing the word “climate.”[61] The program facilitates access to climate resources and provides funding opportunities to the 567 federally recognized tribes through competitive awards to study and plan for climate resilience. On the TCRP main page, the terms “climate” and “climate change” were completely removed from the main text and the sidebar. For example: “Climate Change Indicators” became “Environmental Indicators,” the “Tribal Student Climate Change Photo Contest” was changed to the “Tribal Student Resilience Photo Contest,” and the “Tribal Climate Change Adaptation Program Awards” are now titled “Tribal Resilience Program Awards.”

The National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences changed the term “climate change” to “climate” on its Global; Environmental; Health; pages. Links; to; an; educational fact; sheet; titled ”Climate; Change and Human Health”; were; removed,; reducing; access; to; the; resource.[62]

Rhetorical shifts on webpages are not changes in policy by themselves, but removing mentions of climate change and related terms obscures the public’s understanding of the issue and reduces the informational resources available to them. Those who are not familiar with the common language replacements described above may misunderstand program and agency goals and intentions.

Changes to Agencies’ Overall Presentation of Climate Change

Many federal agencies have established prominent climate change sections on their websites to highlight their work and overall position on climate research and policy. Changes to these pages reflect large-scale shifts in agency missions and priorities on climate change.

The DOI substantially reformatted and removed informational text from its main climate change page. Among the removals was a portion of a paragraph warning that, “climate change affects every corner of the American continent. It is making droughts drier and longer, floods more dangerous and hurricanes more severe.” A “Resources” section with six links to other government climate change pages was added, increasing access to the corresponding pages, but providing no additional description or contextualizing information. On the other hand, an extensive section was removed that detailed the framework through which the DOI’s bureaus coordinate on climate change issues, providing information and links pertaining to the “Climate Change Response Council,” “Eight DOI Regional Climate Science Centers,” and “A Network of Landscape Conservation Cooperatives.”[63]

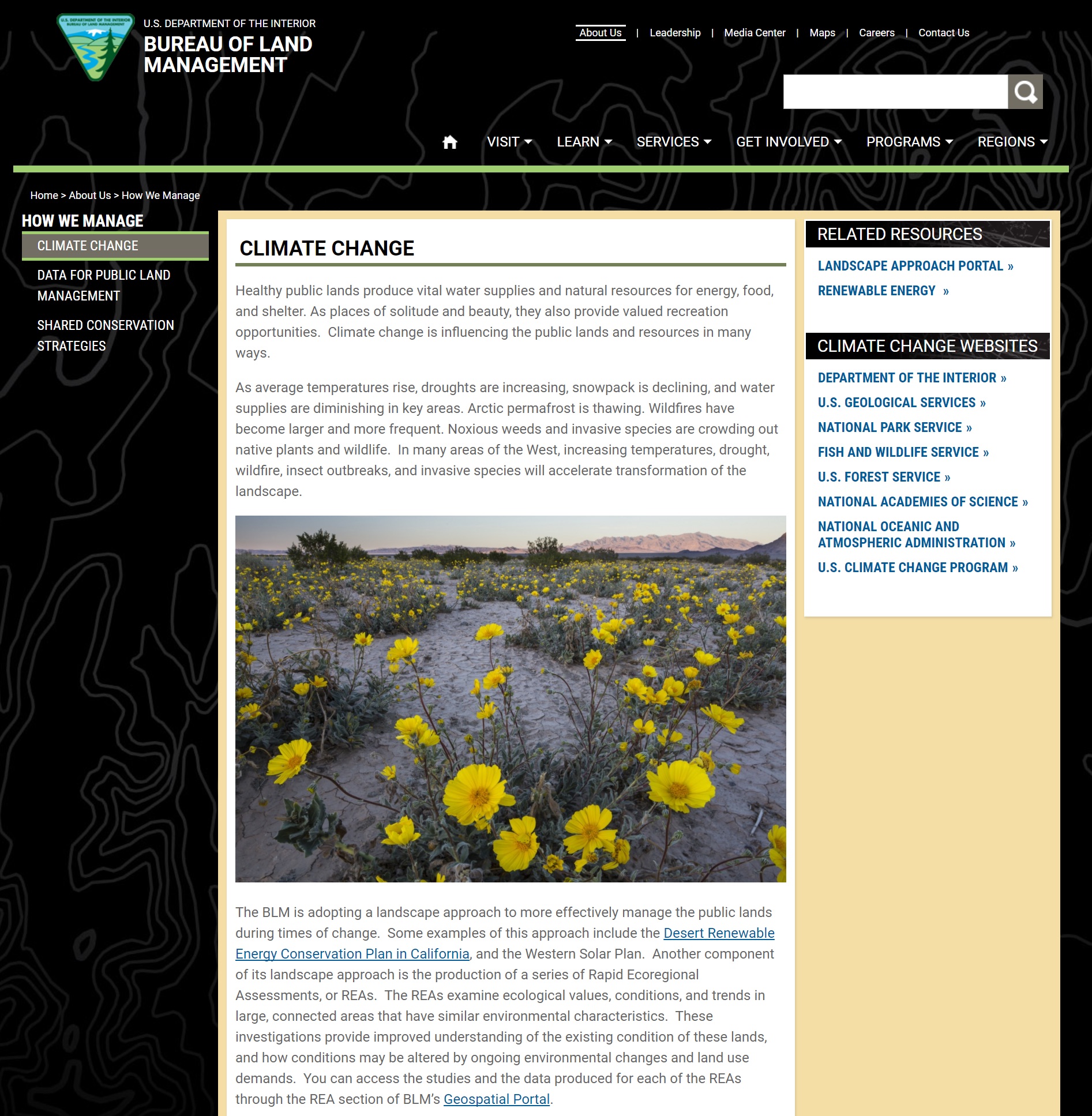

On another part of the DOI site, BLM entirely removed its climate change page (Figure 6). The page stated that “the BLM is adopting a landscape approach to more effectively manage the public lands during times of change” and provided examples of the approach by linking to resources about the Desert Renewable Energy Conservation Plan in California and BLM’s Rapid Ecoregional Assessments. The page also linked to the DOI and other federal Web resources on climate change and renewable energy. The removed page further stated that in addition to adaptation strategies, BLM is working on climate change mitigation by “working with local communities, state regulators, industry, and other federal agencies in building a clean energy future by providing sites for environmentally sound development of renewable energy on public lands.”[64]

In early December, the DOI’s National Park Service removed 92 documents describing national parks’ climate action plans from its website.[65] The plans, detailing how national parks are currently responding and will continue to respond to climate change, are prerequisite for becoming a Climate Friendly Park member. Following the release of EDGI’s report and news media attention, NPS responded by stating that the plans had been removed in order to comply with provisions of Section 508 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, making “electronic information and technology accessible to people with disabilities.”[66] The agency further stated that it intends to return compliant content by the government-wide January 18, 2018 deadline. While increasing usability standards is important for equitable content access, if compliant replacement content had been prepared in advance, the agency would not have had to make valuable resources unavailable simply to remain in compliance with law.

Of All Agencies, the EPA has Removed the Most Climate Web Content

The most significant reduction in access to an agency’s climate change information occurred when the EPA made substantial alterations to its climate change website on Trump’s 99th day in office, which was also the day before the People’s Climate March.[67] As multiple EPA climate change subdomains began redirecting to a notice stating “this page is being updated,” the EPA issued a statement announcing the overhaul of its website to “reflect the agency’s new direction under President Donald Trump and Administrator Scott Pruitt.”[68] The removed EPA climate change domains included extensive information on the EPA’s work to mitigate climate change, as well as details of data collection efforts and indicators for climate change.

Almost all of the removed information could still be found on the January 19 snapshot, which is a mirror of the EPA’s website from the last day of Administrator McCarthy’s tenure that the EPA put up on its website and linked from its homepage on February 15th. The EPA overhaul notice included a link to the January 19 snapshot stating that the “screenshot of the last administration’s website will remain available from the main page.” This sentence originally included the words “as required by law,” but they were removed within hours of the statement’s release. The legal consideration here likely refers to the numerous Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests that were filed requesting historic versions of the EPA website. Indeed, if the EPA received three or more FOIA requests for the Obama-era EPA website, the “Beetlejuice” provision of the updated FOIA legislation would legally require the EPA to make the website snapshot accessible online.[69]

The EPA’s notice that an overhaul was in progress did represent some degree of transparency, yet it failed to note which domains and pages were being removed or altered. Moreover, it was posted the same day that the overhaul began, preventing stakeholders from being able to download and archive valuable pages and information. Because URLs redirected to the overhaul notice and not to the new location of the pages in the January 19 snapshot, links to these pages from government and non-government websites throughout the country and the world suddenly ceased connecting people with useful climate change resources. And because no notice for the change was given, there was no time to alter these links, significantly reducing the public’s access to these resources the day before the People’s Climate March.

While the EPA’s January 19 snapshot made much of the removed climate change information available, even if access was significantly reduced for the reasons stated above, certain parts of the EPA’s website were rendered completely inaccessible. One such example is the “Student’s Global Guide to Climate Change” website (Figure 7), which was not accessible from either the EPA’s live website or from the EPA’s January 19 snapshot once the overhaul began, likely due to an error in copying over this portion of the website to the snapshot.[70] Missing information from the snapshot is problematic from a data preservation and accessibility standpoint and may have legal implications, as discussed above. This kind of poor management of Web resources has left dead links and inaccessible pages, and has generated confusion.

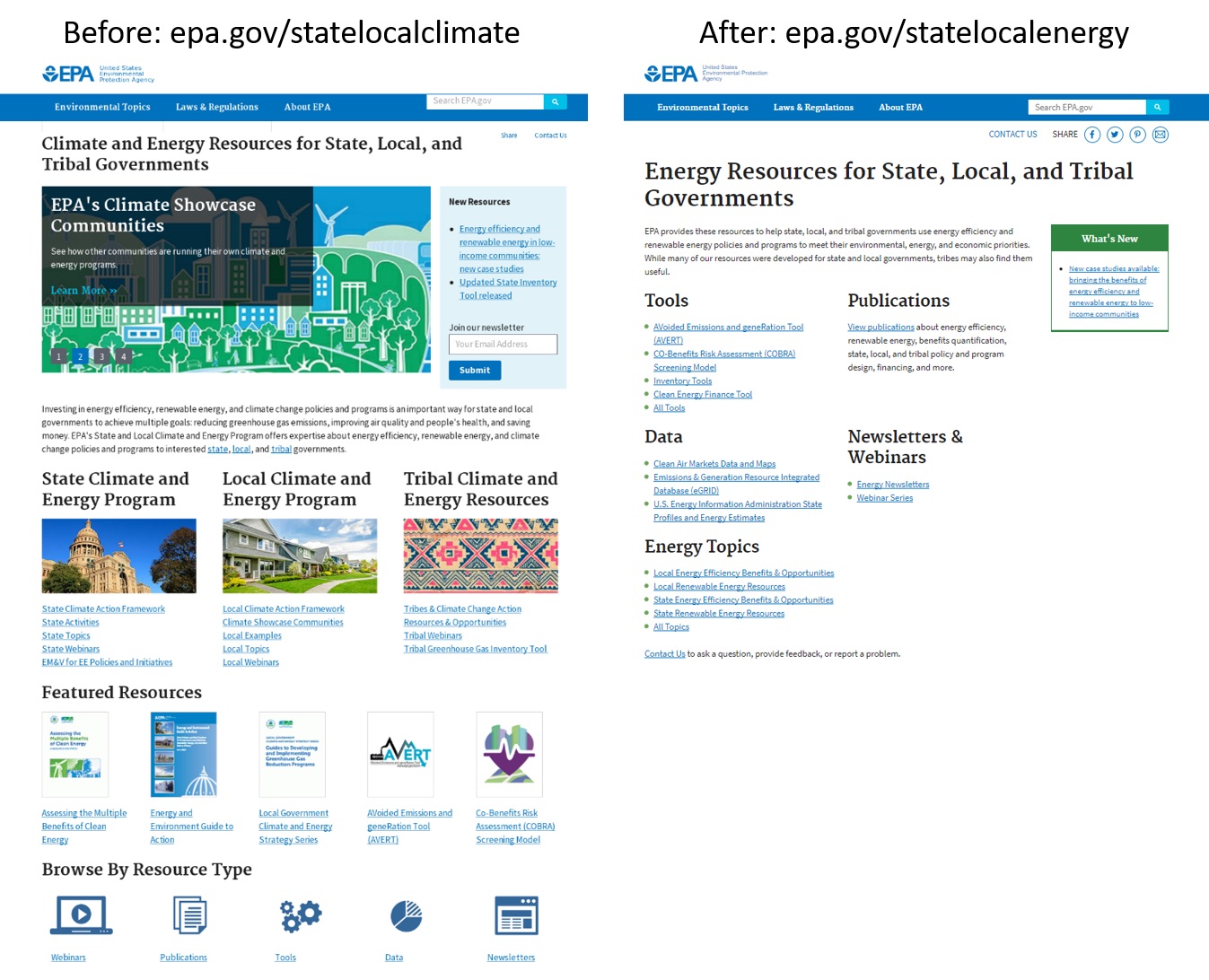

One of the websites removed on April 28 was titled “Climate and Energy Resources for State, Local, and Tribal Governments” and was 380 pages in size (Figure 8). In the first example of returned content, about three months after the removals, a new website titled “Energy Resources for State, Local, and Tribal Governments” was launched, replacing the previous site.[71] Over 200 webpages providing climate information were omitted from the new release and multiple pages, including the homepage, were substantially altered, removing mentions and descriptions of climate and climate change. Some webpages remain unchanged and have been moved from the previous to the new website. For example, all the Web tools, like the AVoided Emissions and geneRation Tool (AVERT), were preserved. Critically, all URLs from the previous website now redirect to the new website’s homepage, which means that links to the previous website have lost their value and specificity.

The EPA has yet to clearly communicate its reason for what has turned out to be a major website overhaul. That content is being returned to the official EPA website but climate information is being systematically left out suggests an intention to manipulate the scientific and policy debate over climate change by restricting public access to information.

Following EDGI’s reporting of the website replacement, seven Democratic senators wrote a letter to EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt asking that the previous “Climate and Energy Resources for State, Local, and Tribal Governments” website be returned and that an explanation for the initial removal be provided.[72] The EPA did not respond to the letter, which argued that “the decision to eliminate these federal resources puts lives at risk and will translate into increased future costs for the states, municipalities, and tribes that rely on these resources to respond to changing environmental conditions.”

One example of how the loss of EPA climate change resources has substantive practical impacts is the targeted reduction of access to the EPA’s Climate Change Adaptation Plans, through link and document removals.[73] The Plans, which are much more difficult to find now on the EPA’s site, warned of the potential for hurricanes to flood Superfund toxic waste sites, as occurred during Hurricane Harvey in Texas. State officials, experts, and others responding to the hurricane and to future natural disasters have less access to the Plans’ advice on how to prepare for flooding, made more severe by the earth’s changing climate, and protect people against toxic chemical exposure.[74]

Beyond reducing access to actionable information, removing public Web resources can undermine democratic institutions such as notice-and-comment rulemaking.[75] Also among the April 28 removals, was the EPA’s website for the Clean Power Plan, President Obama’s defining regulation in the fight against climate change.[76] Months before the EPA’s proposed repeal of the rule, the website was removed and its URL began redirecting to a single page about President’s Trump Executive Order on Energy Independence, which called for a review of the Plan. The previous website hosted and aggregated resources for the public to understand the Clean Power Plan and for states to develop emissions plans. Spanish-language Web resources, like fact sheets and community information, were removed without being archived, likely due to the same errors as the Student’s climate change site removal. The replacement page links to the Executive Order notice, the Federal Register, and related news releases, but provides almost no information justifying or explaining the shift in policy. The new page does not mention that a previous site existed and, importantly, does not point to the archived version of the Clean Power Plan website.

A student, policymaker, scientist, or member of the public interested in writing a public comment can make a difference as all comments need to be accounted for equally. However, removal of Web content and obfuscation of resources makes it more difficult for those interested in engaging in the rulemaking process to provide an informed, evidence-based comment. Anyone valuing the idea of democratic policymaking should demand that public Web resources relevant for regulations should remain readily accessible to the public, whether regulations are being proposed or rolled back.

In most cases, the best and quickest way to learn about an agency’s priorities, operations, and policy perspectives is to access its website. By restructuring websites and changing Web content, agencies are signaling what is and is not important to them and how they would like the public to engage. Removal of climate information disconnects the public from important resources for understanding climate science and policy, and inhibits informed actions they might take as a result. Moreover, if done without explanation, it isn’t clear if alterations have an underlying scientific basis or are politically motivated.

VI. IMPORTANCE OF ACCURATELY DESCRIBING FEDERAL WEBSITE CHANGES AND MEDIA PORTRAYAL

Websites can change in a variety of ways,[77] from straightforward text edits to confusing webpage overhauls and URL redirects. It is also not always obvious who is responsible for making the changes and what the review process is before a change is published. Paying attention to these distinctions is important in order to make sure that focus remains on the correct issues.

The journalism community, in particular, has covered changes to federal websites since President Trump took office, working to contextualize the shifts in rhetoric and reduction in access to important digital resources as warning signs and indicators of changing policy. This reporting on issues of information and data governance and access is an important public service. However, journalists have occasionally misrepresented the nature of the changes that are occurring by attributing changes to political appointees without evidence and by using improper terminology or misunderstanding the nature of the changes.

Attribution of Changes

Without additional information, it is often impossible to tell whether changes were made by career agency employees, agency political appointees, members of the Trump administration, or anyone else. The distinction between self-censorship, in which career staff attempt to make their offices appear less at odds with the administration’s stated policy goals, and changes that were ordered by political appointees at an agency or the White House, is not trivial.

In certain cases the Trump administration’s involvement is clear, as in the White House website changeover and the overhaul of the EPA’s climate change website, which was accompanied by a statement that the changes reflected “EPA's priorities under the leadership of President Trump and Administrator Pruitt.”[78]

Reporting by The Washington Post, however, suggests that other changes, such as renaming of the DOE’s “Clean Energy Investment Center” the “Energy Investor Center” and the associated changes to the Center’s webpages, were an act of self-censorship. The Post writes, “Energy spokeswoman Lindsey Geisler said these changes were not ordered by the Trump administration but were made by career staff to ‘better reflect the broader focus of the project, which includes all traditional and nontraditional energy sources.’”[79]

FHWA’s rebranding of their program by switching “climate change” to “resilience” in their name occurred on December 13, 2016, before the inauguration, and was the result of weeks-long “internal discussions,” according to one of their spokespeople. Though we cannot rule out early communication with transition team members or future Trump administration officials, the evidence suggests that the initiative to change originated from within FHWA and not the Trump administration.

While these cases were identified as originating from career officials, it has often been impossible to know the source of the orders for other website changes that have been covered by the media. Cases like this, however, demonstrate that we cannot assume that all website alterations originate from the administration or from political appointees.

The news media has sometimes attributed the changes to the Trump administration without corroborating evidence, which misleads the public and distracts from what may really be occurring. For example, a ProPublica article, originally titled “Child’s Play: Team Trump Rewrites a Department of Energy Website for Kids,” implied that the language changes on the EIA site were ordered by political appointees. ProPublica updated the article and its title to remove explicit attribution to the Trump administration after EIA, which is an independent agency whose publications are not subject to external review, responded by saying, “contrary to the headlines and content of the articles, EIA has never been contacted by anyone in the new administration regarding the content of any part of EIA’s website.”[80] In another case of misleading reporting, a Guardian article titled “Trump is deleting climate change, one site at a time,” which provided several examples of changes across federal agencies, overgeneralized by stating that “the administration has taken a hatchet to climate change language across government websites,” not providing evidence for the administration’s involvement or noting the possibility for self-censorship.[81] Getting the story right helps document the internal processes and shifts in priorities that are occurring at agencies and provides an important lead for future investigations.

Misuse of Language and Misunderstandings

In some cases, journalists have described website changes in imprecise and exaggerated language that can mislead readers about the severity of those alterations. On numerous occasions, articles refer to the removal of “data” in cases where that is not what really occurred.[82] The term “data” is often used loosely, leading readers to assume worst case scenarios, such as the removal of primary source data sets (e.g. files of buoy or satellite measurements) from websites, or even from government servers, which has not occurred. In fact, in essentially all cases thus far, the word “data” has been used to refer to either text on a webpage, a webpage, or a document that contains text and images, which would more accurately be described as Web information or content.

Moreover, the EPA, State Department, and White House, for example, all have publicly accessible archives of their Obama-era websites, so for many observed changes on those websites it is more correct to say that data or information has been made less accessible, or has been removed and archived, rather than stating that data or information has been “deleted,” as some journalists have done.[83] Still, not all agency website archives represent a complete record, as demonstrated by the missing Students’ website from the EPA’s January 19 snapshot. Such cases could be referred to as page deletions and have, thus far, been the most substantial reductions in information access.

One Guardian article claimed that arctic “data” was “deleted” from government websites, merging both of the language errors described above.[84] In fact, the article’s author was only referring to removals of President Obama’s White House webpages and documents, which remain publicly archived. No evidence of data deletions was presented.

Distrust of agencies, coupled with confusing changes and lack of proactive agency explanation, has sometimes led to a public outcry based on incorrect reasoning. For example, after the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) changed their search engine’s properties, the number of results for the same search term dropped from the thousands to the hundreds.[85] Although the entire search engine was affected by these changes, the reduction in the number of search results for the term “climate change” was given special attention in a series of tweets. The social media response as well as subsequent news media coverage[86] confused a few important points. First, articles stated that information was taken offline, when there was no evidence that webpages, documents, or data were removed, only that the search results that linked to Web content were affected. Second, the specific focus on climate change implied that there was a targeted removal of climate information. That the entire search engine was affected refutes this implication. Third, there was no evidence that the Trump administration was directly involved and several USGS spokespeople stated on record that there was no political interference.

USGS failed to mitigate this confusion by not proactively announcing and explaining the changes to their search engine. But in order to hold USGS—as well as other agencies—accountable, we must have an accurate understanding of how changes to websites really affect public access to information.

* * * * *

Describing changes to federal websites accurately can be a subtle exercise, yet it is important to get it right for multiple reasons. Attributing changes to the wrong sources and/or using inaccurate language to describe website changes misrepresents the degree to which transformations are occurring at these agencies and distracts the public from the real concern of information and resource removal from websites. Furthermore, presenting wrong or misleading information drains the news media’s bandwidth and wastes limited resources on error correction. Without accurate information, members of the public and advocacy groups who champion environmental and Web accountability via elected officials or legal proceedings may pursue the wrong ends. More generally, inaccurate reporting threatens public faith in the news media as an objective source of information about the new administration, and the lack of such a trusted source undermines democratic institutions.

VII. STATE AND LOCAL RESISTANCE TO TRUMP ADMINISTRATION CLIMATE CENSORSHIP

The current administration has restricted U.S. efforts to address climate change through actions such as withdrawing from the Paris climate accord and attempting to repeal the Clean Power Plan. In response, many state and local governments are leveraging their own authority and influence to reduce carbon emissions. Fourteen states and the U.S. territory Puerto Rico have formed the United States Climate Alliance,[87] whose members are committed to upholding their state’s responsibility under the Paris climate accord by decreasing their greenhouse gas emissions to 26-28% below their 2005 emissions by 2025. On the municipal level, 382 cities have joined the Climate Mayors[88] to uphold the Paris climate accord and more significantly address greenhouse gas emissions and sustainable practices. For instance, Los Angeles has committed to a 45% reduction below its 1990 emissions by 2025, and an 80% reduction by 2050.

Municipalities and states have long been at the forefront of innovatively addressing climate change issues, particularly when the federal government is unable to do so. Following the United States’ failure to ratify the Kyoto Protocol in 2005, the U.S. Conference of Mayors created the U.S. Mayors Climate Protection Agreement,[89] which now has 1060 signatories, to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in each signed mayor’s city in line with the Kyoto Protocol. Since the mid-2000s, several states have formed regional alliances to create greenhouse gas emissions reductions plans, such as the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative[90] in northeastern states and the Western Climate Initiative.[91] Today, many state and cities are banding together to address the changes in public access to environmental information detailed in this report.

The mayors and governors involved in efforts to preserve public access to information on climate change argue that an informed public is one of the first steps to protecting the environment and addressing climate change. People need to understand what climate change is, what we can do to slow it, and how we can mitigate its effects.

In California, the state senate sought to protect federal environmental and climate data by proposing a bill that would have required the Secretary for Environmental Protection to make available online federal scientific information and data that was deemed at risk.[92] While Governor Brown vetoed the bill due to concern about state authority to protect federal whistleblowers, he did announce his support for protecting and providing access to federal data and information.

Concerned by the possibility of lost climate information, the City of Chicago copied parts of the EPA’s climate change website, and is currently hosting it at the URL http://climatechange.cityofchicago.org. A banner on the mirrored sites states that “while this information may not be readily available on the EPA’s website, in Chicago we know climate change is real. We are joining cities around the country to make sure citizens have access to information on climate change.” Chicago also established instructions and a data repository in GitHub so that other cities could copy and host the webpages; sixteen cities across the U.S. currently host this information on their local government websites.[93] This kind of action by local governments is crucial for holding the federal government accountable.

COMMENT: A perspective from Lioneld Jordan, mayor of Fayetteville, AR, about the role of cities in preserving digital climate information

Climate change poses a very serious threat not only in terms of sea level rise for coastal communities but also for the heartland of America. Heat and drought stress, along with flooding from more intense storms, are real climate change consequences that we are facing in Fayetteville, Arkansas. We are committed to working with leaders of other cities, states, universities, and businesses to identify these threats and to make our communities more resilient to them. This is a matter of national security and social justice. Through our work to develop Fayetteville’s Energy Action Plan, we also recognize that reducing carbon emissions and combating climate change represents a significant economic opportunity for our city and our nation by investing in a low-carbon economy and creating good jobs in energy efficiency and renewable energy.

Preserving access to the Environmental Protection Agency’s data and scientific assessments of climate change is fundamental to our understanding and collective will for action. This is true for the citizens of Fayetteville, Arkansas and across the United States. Policies on how to respond to climate change may be debatable but the underlying science on why climate change is happening and what impacts it may have are not.

VIII. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Significance of Website Changes and What’s to Come

Federal websites are often the public’s primary source of information about agency roles and priorities on issues and provide some of the richest educational materials on important science and policy topics, from climate change to environmental justice. When people visit federal websites, however, they see only the current version, not the record and progression of changes that lead up to it. They have no way to see how their access to information has been altered.

Our examination of changes across many federal agencies over the first year of the Trump administration demonstrates a systematic reduction in access to climate information and content. Links have been cut from pages or rendered useless, language has been changed to alter emphasis and drop mentions of climate-change-related topics, and entire climate websites have been removed and made significantly less accessible.

While we have not observed any removal of climate data, the trend of website alterations signals a change in approach to federal environmental, climate, and energy research, practice, and policy, deemphasizing the importance of renewable energy, the harms of continued use of non-renewable energy sources, and the potential detrimental effects of climate change overall. Moreover, these changes have made it harder for the public to gain access to years of well-researched and organized information paid for by their tax dollars, information that is crucial in helping inform the important discussions on how to best mitigate and adapt to the effects of climate change.

The altered and removed Web resources predominantly affect policymakers attempting to understand local, state, tribal, and international climate action. However, the changes also hamper those learning about climate science or educating others about it.

The result is an overall diminishment of democratic institutions like notice-and-comment rulemaking. Reduced access to public Web resources about agency regulations that are being proposed or repealed, and the benefits or harms of those regulations, inhibits people’s ability to research relevant topics and provide informed comment. As every public comment needs to be addressed in the rulemaking process, providing open access to information contributes to an evidence-based policy discussion. The removal of the EPA’s Clean Power Plan website in advance of the Plan’s proposed repeal, obscuring compiled state emission policy information from those interested in researching the Plan, is one example of how democratic policymaking is undermined.

Why are these federal agencies putting so much effort into "science cleansing" instead of using time and resources to fulfill agency responsibilities, such as protecting the environment and advancing energy security? Removing information regarding climate change from federal websites does not affect the reality of climate change, but may serve to obfuscate the subject and inject doubt regarding the scientific consensus that climate change is happening and that it is caused by human activity.

In the short term, revealing these rhetorical tactics and shining a spotlight on important information and data governance questions increases government accountability and informs the public of agency priorities under the Trump administration. Looking forward, however, if programs and offices are defunded, as Trump’s proposed budget signals, then the continuity of data collection, research, and policymaking pertaining to climate change may be disrupted in long-lasting and harmful ways. More than just protecting the public presentation of climate change information, we must take great care to preserve our broad efforts to understand and respond to this threat in an informed manner and continue to bolster the important public discourse about how to best respond to the harms of climate change.

COMMENT: Gretchen Goldman, Union of Concerned Scientists, Research Director for the Center for Science and Democracy

Before President Trump was inaugurated, activists and scientists scrambled to archive data and webpages out of concern that the incoming administration could remove, tamper with, or otherwise upend the rich depositories of scientific information on federal agency websites. There was, after all, precedent for such behavior. Under past administrations, government scientific information has been politicized. And given Trump’s statements as a candidate, there was no reason to assume his administration would respect scientific integrity and the role it plays in the federal scientific enterprise.

In the past year, the changes identified by EDGI and others on government webpages have been sporadic but significant. When material on climate change is removed from federal webpages, it matters. It prevents the public from accessing vital information about climate adaptation and other resources useful in preparing for climate-related impacts. It also sends a signal to the American public and international community about the priorities of the United States.

The scientific community gets the message loud and clear: study of climate change is no longer welcome within the government enterprise. Under the current administration, a federal scientist simply doing his or her job might be viewed as defiant or disloyal. Such an environment has a chilling effect on the entire scientific community. Researchers will now second-guess the direction of their research and the use of climate change in their work. This could vastly restrict the kind of research questions scientists ask and the areas of research they pursue. Indeed, we’ve already observed several cases of self-censorship where communication of scientific work has been altered to avoid reference to climate change, even without any direct political interference.

The frightening long-term consequence of such censorship is that we may have fewer scientists working on one of the most complex and urgent scientific problems of our time. We need scientists to continue studying climate change and other politically contentious scientific fields. Without current and robust scientific information feeding into policy processes, decision-makers will be ill-prepared to make evidence-based choices that determine our future.

Website changes thus have huge repercussions for us all. While a single change may seem relatively insignificant, each removal or alteration of scientific information brings us closer to a government based on fiction, not fact. Such a reality would be devastating for science and for our democracy.

Digital Information Governance Practices

As scientists make progress in their research, new treaties are ratified or repealed, the federal budget is amended, and agency priorities are updated, these changes are reflected on federal websites. So what, then, differentiates the natural and healthy turnover of digital information from a regressive and revisionist restructuring of Web content?

In general, agencies and offices must take it upon themselves to determine how the presentation of Web information aligns with their mission and charters. They must critically ask if an alteration or removal of content will harm or benefit the public and the users of their sites. Moreover, public Web content should be valued not only for its utility for education, as well as scientific and policy research, but also for its historic worth. In the case of climate change, public information reflecting the overwhelming scientific consensus, and supporting the health and safety needs of communities, must be maintained.

Federal agencies are best positioned to oversee their websites and decide what to update, but in most cases these decisions are not made transparently in a way that the public can easily observe or even become aware of.

To address these information governance issues, there are several existing guidelines, regulations, and laws, in addition to new policies being proposed.[94] For instance, a current Office of Management and Budget memorandum on “Policies for Federal Agency Public Websites and Digital Services” states that “when significant changes occur, such as a website redesign, the organization must provide information to the public about the changes.”[95] If passed, proposed legislation like the Preserving Data in Government Act[96] would require federal agencies to maintain public access to data sets and prohibit altering or removing data sets without sufficient public notice. New National Archives’ Web records policy guidelines, updating the dated 2005 guidelines, would help ensure that agencies properly archive Web records, inform the public of important changes to Web content, and ensure continued accessibility of important records.[97]

More generally, we recommend the following practices for more just and accountable data and information stewardship:

- Transparency. Especially for major website overhauls, but for smaller updates to webpages as well, agencies should detail the scope of the pages that will be affected and clearly explain the reason for planned alterations in a public statement, well in advance of the changes actually being made.

- Responsible Web archiving. Federal agencies should not alter or reduce access to Web content before they have created a log to thoroughly document their intended changes and ensured that the content is preserved and, for significant alterations, made accessible through a public archive.

- Valuing Web resources. Web resources should be valued in terms of their educational importance, how much they enable historical understanding, and their advancement of scientific and policy research. Records schedules and records governance broadly should reflect these uses.

- Distributed Web archiving. Federal agencies should work with growing civil society movements to rethink the way we organize, steward, and distribute data, Web resources, and online information.

- Environmental data justice. Federal environmental agencies should work to create digital infrastructure through which communities can determine what kinds of data are collected and presented about them, in response to which issues. This includes proactive efforts to identify and accommodate those who access federal Web information, as well as offering communities the right to refuse consent to data collection.